|

----------------------------------------------------

----------------------------------------------------

"Berimbau"

By N. Scott

Robinson and Richard P. Graham

The

Brazilian berimbau de barriga, or simply berimbau,

is a gourd-resonated, braced musical

bow of African origin. The instrument consists of a 4'–5'

(1.2 m–1.5 m) branch of biriba, bamboo, oak

or other wood bent into an arc. The bow is strung with a

single metal string, usually recycled from an industrial

use.

Attached

to the convex back of the bow with a small loop of string

is a gourd resonator, although coconut, calabash or a tin

can is occasionally substituted for a gourd. The string

loop also serves as a bridge, dividing the metal string

into two sections. The little finger of the musician’s

left hand (assuming a right-handed player) passes underneath

the string loop to hold the berimbau.

The string

is struck with a thin stick called a vaquita or

vareta, which is held in the player’s right

hand along with a small basket rattle called caxixi.

A small coin (dobrão) or stone (pedra)

held between the musician’s left thumb and index finger

is pressed to the string, resulting in a pitch change of

about a minor or major second above the berimbau’s

fundamental tone.

The berimbau

originated in an early nineteenth-century Brazilian slave

culture. Several historical notices and depictions from

this period demonstrate the continued presence of a variety

of central African musical bows (Koster 1816, 122; Graham

1824, 199; Walsh 1830, 175-176; Debret 1834, 39; Wetherell

1860, 106-107). Popular among African-Brazilian vendors

and street musicians, these musical bows were known by African

names such as urucungu, madimba lungungo,

mbulumbumba, and hungu (Shaffer 1976,

14; Kubik 1979, 30). As a result of pan-African technology-sharing,

organological traits of these various musical bows were

fused to create a single African-Brazilian instrument (Graham

1991, 6).

Sometime

in the late nineteenth century, this new musical bow received

a Lusophone name—berimbau de barriga, or

"jaw harp of the stomach"—and entered a new

cultural context, the African-Brazilian martial art form

known as capoeira (Kubik 1979, 30-33). Beginning

at least as early as the eighteenth century, capoeira

was fought to the music of an African-derived hand drum

or to simple handclapping. Capoeira is now fought

to the toques (rhythms) of the berimbau,

which accompany the songs known in Brazil as cantigas

de capoeira.

The musical

ensemble employed in contemporary capoeira features

one to three berimbaus, an atabaque (conical

hand drum), a pandeiro (tambourine) and an agogô

(double bell). Where multiple berimbaus are employed

in an ensemble, they are often tuned to separate pitches.

In Salvador de Bahia, the cultural epicenter of capoeira,

different names are used for berimbaus of various

sizes, including viola (small), medio

(medium) and gunga (large) (Lewis 1992, 137). From

the 1940s, a number of capoeira schools in Bahia

began to paint their berimbaus with colorful stripes

and other decorations, reflecting their pride in their individual

academias (traditional capoeira schools)

(Shaffer 1976, 26).

Richard

P. Graham

Boston, Massachusetts

The

Berimbau in Popular Music

Besides

its close association with capoeira, the berimbau

has long been used in a variety of Brazilian folk and popular

music forms, such as samba de roda, carimbo,

bossa nova, afro-samba and tropicalismo.

Art music composers such as Mario Tavares (Gan Guzama),

Luiz Augusto Rescala (Musica para Berimbau e Fita Magnetica)

and Gaudencio Thiago de Mello (Chants for the Chief)

have also written music for the instrument.

The berimbau

experienced a creative renaissance in 1960s Brazilian popular

music, followed by its spread to areas outside Brazil and

its use in 1970s international jazz. Although the international

diffusion of capoeira was a phenomenon that contributed

to the spread of the berimbau, this occurred only

after the instrument had already spread through popular

musics. As a result of Brazilian popular musical movements

in the 1960s, the berimbau began to be heard internationally

independently of capoeira. Baden Powell and others

brought the berimbau to the attention of musicians

outside Brazil in afro-samba songs that mimicked

the sound and rhythm of the berimbau on the guitar.

In 1962, Wilson das Neves of the samba-jazz group Os Ipanemas

used the berimbau extensively in a most creative

manner on their self-titled debut recording. Percussionist

Dom um Romão used the instrument on the track "Birimbau

(Capoeira)" in a samba-jazz big band on his debut recording

Dom Um in 1964. In 1965, Astrud Gilberto recorded

a jazz-bossa nova version of Powell’s "Berimbau"

that featured Dom um Romão on berimbau on

the recording Look

to the Rainbow. Gilberto Gil

recorded an important tropicalismo album in 1968

(titled Gilberto Gil), which featured the berimbau

with electric guitars on the song "Domingo no Parque."

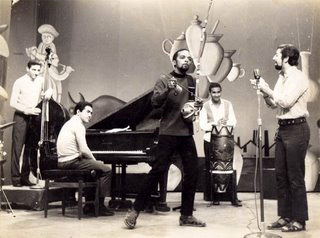

Also in 1968, percussionist Naná

Vasconcelos was featured on Brazilian TV playing berimbau

with the group Trio

Nordeste. An unusual recording by

the vocalist Joyce of the Heitor Villa Lobos piece "Bachiana

Nº 5" for the 1970 television film Irmãos

Coragem (released on a soundtrack LP of the same name)

featured non-traditional berimbau. By 1970, the

berimbau had entered a variety of popular musics

in both Brazil and the United States.

Wilson

das Neves recording with berimbau in 1962 on the

LP Os Ipanemas.

Several

expatriate Brazilian percussionists began the process of

reinterpreting the berimbau, using it outside of

capoeira in 1970s jazz, and this resulted in innovative

technical and organological developments. Airto Moreira,

Dom um Romão, Guilherme Franco and Naná Vasconcelos

[Juvenal de Hollanda Vasconcelos] had explored the possibilities

of using the berimbau in jazz, and they were followed

by Paulinho da Costa and Djalma Corrêa (and Papete

[José de Ribamar Vianna] and Chocolate Do Mercado

Modelo in Brazilian pop). Airto Moreira, who left Brazil

in 1968, played the berimbau on recordings by Miles

Davis in 1969, his solo recording in 1970, and played with

the group Weather Report in 1971. Dom um Romão replaced

Moreira in Weather Report and continued to use the berimbau

during a Japanese tour in 1972. Subsequently, Romão

developed an electric berimbau, which greatly increased

the volume of the instrument and allowed for subtle changes

in its timbre through the use of signal processors. Guilherme

Franco had been using the berimbau in an experimental

percussion trio in Brazil in 1972. After moving to New York,

he played the berimbau on jazz recordings by Archie

Shepp and McCoy Tyner and performed with The International

Percussion Quartet. After performing on berimbau

on Brazilian TV in 1968 with Trio Nordeste, Naná

Vasconcelos first recorded on the berimbau with

Milton Nascimento (for the film soundtrack Tostão,

a fera de ouro) and then with Luíz Eça

and Sagrada Família both in 1970, subsequently playing

the berimbau with Argentine Gato Barbieri in 1971,

and made three successive solo recordings between 1971-1973

in Argentina, France, and Brazil featuring extended improvisatory

solo pieces. Subsequently, non-Brazilian percussionists

extended the process of reinterpretation, playing the berimbau

in jazz. Among them were Luis Agudo and Onias Carmadelli

[also spelled as Camardelli] both from Argentina, Okay Temiz

from Turkey, African-American Bill Summers, American jazz

drummer Shelly Manne, Ray Armando from Puerto Rico, Curt

Cress from Germany, Alan Lee from Australia, and Marta Contreras

from France, among others.

Naná

Vasconcelos and Trio Nordeste, Brazil TV, 1968

Naná

Vasconcelos & Gato Barbieri, 1971

The

use of the berimbau in jazz provided a nontraditional

context for contact, in which percussionists with little

or no experience with capoeira could freely exchange

ideas about berimbau techniques. Luis Agudo moved

to France in 1970, where he built his own berimbau

with a double caxixi and experimented with African,

Brazilian and Argentinean rhythms. While touring Europe,

Agudo met Okay Temiz in Sweden in 1974 and instructed him

in how to build a berimbau. By 1975, Temiz had

developed a completely new technical approach to the berimbau,

involving numerous effects pedals, microphones and a free-hand

grip similar to that used for the violin, where the instrument

is held between the chin and the shoulder, so that both

hands were free for playing. A similar cultural exchange

occurred through contact between Naná Vasconcelos

and percussionists in Italy and Japan. In the 1990s, Vasconcelos

performed a series of solo concerts and held workshops in

Japan and Italy. As a result of personal contact with Vasconcelos,

percussionists Seichi Yamamura of Japan [sometimes spelled

as Seiti Yamamura] and Peppe Consolmagno [Giuseppe Consolmagno]

of Italy began to play the berimbau in a style

heretofore peculiar to Vasconcelos, effectively contributing

to a kind of berimbau performance lineage.

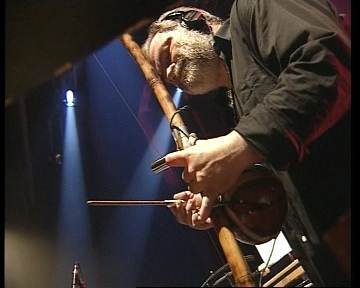

Guilherme Franco

- The International Percussion Quartet, c. 1970s

New

Berimbau Techniques

By

the 1990s, a number of organological developments and new

techniques were evident in the way that the berimbau

was played in popular musics. Tuning became an issue when

the berimbau was played in new musical contexts

where pitch was a consideration. Some musicians, such as

Vasconcelos and Temiz, actually tied the gourd resonator

to the wooden bow in a new manner, so that it was fixed

in place, keeping the pitch accurate. Brazilian Dinho Nascimento

built a large bass berimbau, called berimbum,

which used the string and tuning hardware of an acoustic

bass (American instrument makers Gino

Zenobia and Matt

Collins and German maker Anklang

Musikwelt continue to produce berimbau with

built in tuning hardware).

Dinho Nascimento

with berimbum, 2000

Another

organological development consisted of doubling the number

of strings, which required new performance techniques. Double-string

berimbaus were used by Vasconcelos, Temiz and Franco

(who also developed a double-berimbau—literally

two instruments joined as one). Romão, Temiz and

Franco developed electric berimbaus. Temiz also

developed an electric double-string berimbau that

featured the addition of separate microphones and signal

processors for the string, gourd and caxixi. His

technique involved using as many as nine signal processors

simultaneously in conjunction with a free-hand grip, which

allowed the left hand to slide the coin farther up and down

the string, producing many more than the traditional two

pitches. By amplifying each part of the berimbau,

Temiz could exploit other possibilities, such as tapping

on the gourd with the coin, fingers and stick, successfully

producing traditional Turkish rhythms.

Okay Temiz - free-hand

grip & electric berimbau, 1983

Vasconcelos

expanded many technical aspects of the berimbau.

Such technical developments included plucking the string

with the fingers, striking the wood of the bow with the

stone, muting the string, scraping and striking the gourd

and other parts of the instrument with the stick, increasing

the number of pitches from two to three with a special angled

stone stroke, and playing inside the bow with the stick

by alternating between the wood and string, thereby achieving

many kinds of harmonics and percussive effects. He also

redefined the role of the caxixi. Keeping one rhythm

with the caxixi as an ostinato, the fingers of

the same hand played different accents on the string with

the stick. Similar techniques, and others, appear in Luiz

Almeida da Anunciação’s berimbau

method book of 1990. Argentine Luis Agudo and Brazilian

Dom um Romão both employed an unusual technique for

string bending by bracing the gourd against the body while

pulling back on the bow. In the 1990s, Dinho Nascimento

developed a blues-like slide-berimbau technique,

which involved holding the bow against the body in a free-hand

fashion so that a glass slide could be used to bend the

tones of the string. In the 1990s, Italian Rosario Jermano

developed another slide-berimbau technique that

called for a new left-hand grip and the use of a metal guitar

slide in place of the stone or coin. Through both a methods

book and teaching, Jermano’s technique spread to other

musicians in Italy, including percussionist Paolo Sanna.

Regarding

the slide-berimbau, other Brazilian musical bows

and monochords achieve a similar effect despite not being

a berimbau played with an innovative technique.

Airto Moreira experimented with a different musical bow

called berimbau de bacia on Flora Purim's 1974

recording 500 Miles High: Flora Purim at Montreux.

His incorrectly credited berimbau solo on the track

"Cravo e Canela" is in fact a berimbau de

bacia. This instrument is played horizontally by placing

a gourd-resonated musical bow on top of a bucket as an additional

resonator. The player's foot braces the wood of the bow

over the bucket with the string facing upwards. The string

is struck with a stick while the stone slides across the

string to achieve a much more melodic effect than the traditional

berimbau is capable of. Moreira also used this instrument

in duet with a didjeridu on the 2003 CD Life

After That. Antúlio Madureira has utilized the

marimbau de cabraça, a type of archaic Brazilian

glissed monochord, on several neo-traditional and popular

music recordings (refer to the Caetano Velôso track

"Rapte-me Camaleoa" on the Kelly Benevides 2001

CD Tráfego Local for an example of the marimbau

de cabraça in a popular music setting). Also

played horizontally, the marimbau (1 or 2 string

versions, also as marimbal) is not a musical bow

but is played with a stick and a slider achieving a melodic

effect that sounds similar to the berimbau de bacia

(as does the unrelated blues monochord from the southern

USA known as diddley bow or diddy bow). The innovative slide-berimbau

techniques employed on the traditional berimbau

are usually played in a vertical position.

Diddley

bow, monochord from USA

Marimbau,

monochord from Brazil

Rosario

Jermano's slide-berimbau grip, 1999

Rosario

Jermano's slide-berimbau grip

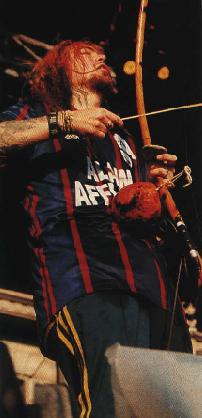

Both

inside and outside of Brazil, the berimbau is still

being used in new ways in popular musics. Brazilian artists

who have recently used the berimbau in heavy metal,

rap, electronica, and rock include Sepultura, Soulfly, Cyro

Baptista, General Frank, Gilberto Gil (with Gustavo di Dalva

on electric berimbau), and Mônica Feijó,

among others. Artists outside of Brazil that have also recently

used the berimbau in new genres include Tim Hurley

(USA, in the punk rock band Red Red Meat), Tim Aquilina

(USA, in the folk trio The Hitmen), Ramiro Musotto (Argentine

who plays tuned berimbau with club music electronica),

Santiago Vazquez (Argentine improvising percussionist),

Alex Pertout (Australia, orchestral and jazz), Mataro Misawa

(Japan, jazz), Joca Perpignan (Israel, in the folk group

Tucan Trio), François Malet (France, jazz), Nuno

Rebelo (Portugal, experimental film/dance/theater), Greg

Beyer (USA, composer of a multi-berimbau minimalist

piece in 2001 called Bahian Counterpoint (Homage à

Steve Reich) as well as commissioning pieces

for elaborately tuned berimbau in duo and sextet),

Douglas Geers (USA, composer of Exit to City for

berimbau and computer in 2003), Taufiq Qureshi

(India, fusion), Frank Colon (USA, jazz), Rich Goodhart

(USA, progressive world-rock), Richard P. Graham (USA, world

music), and N. Scott Robinson (USA, world music). The berimbau

has been used in new age and music therapy genres with recordings

by anthropologist Michael Harner of The Foundation for Shamanic

Studies, among others. The berimbau was also featured

in several films including Anselmo

Duarte's O Pagador de Promessas in 1962 and

the 1993 martial

arts/action film Only the Strong. In several television

commercials during the early 2000s, the automobile company

Mazda even used the capoeira song "Zum Zum

Zum" but changed it to "Zoom, Zoom, Zoom"

and included berimbau accompaniment in the popular

music soundtrack for its advertising campaigns.

Max Cavalera of the

heavy metal groups Sepultura & Soulfly

Conclusion

The

berimbau has become somewhat emblematic of Brazilian

popular culture, its image appearing frequently in murals,

sculpture, jewelry, tattoos and the electronic media. The

diffusion of the berimbau into popular musics outside

of capoeira and beyond Brazil has led to its increased

sophistication and technical diversity as a musical instrument.

Because of the various styles of music in which the berimbau

was increasingly used, new techniques were developed to

better meet the challenges of berimbau performance

outside of capoeira. These new attributes of contemporary

berimbau performance include an increased tendency

toward improvisation, the use of electronics, additional

strings, combinations with new instruments, new rhythmic

styles, and solo performances. Following the innovations

of Brazilian percussionists, many non-Brazilian musicians

who creatively adopted the berimbau did so without

a prior knowledge of capoeira and approached the

instrument solely in the context of jazz and rock. Through

the process of reinterpretation, the increased range of

diverse performance techniques came to better fit the needs

of musicians who used the berimbau in new contexts,

and this facilitated the use of the instrument outside of

capoeira and beyond Brazil.

N. Scott

Robinson

San Diego Mesa College, California

[An

edited version of this article was published as "Berimbau"

in the Continuum

Encyclopedia of SPACE SPACE Popular

Music of the World, Volume 2: Performance and Production.

Edited by John SPACE

SPACEShepherd,

David Horn, Dave Laing, Paul Oliver, and Peter Wicke. New

York: SPACE

SPACE

SPACEContinuum,

2003, 345-349].

Bibliography

Anonymous.

"Okay Temiz." Pozitif (May 1991), 23-24.

________. "Okay

Temiz ile Söyleysi." Dans Müzik Kültür:

Folklora Dogru 62 (1996), 93-109.

________.

"A História do Berimbau" [The History of

the Berimbau]. Revista Capoeira 2, no. 7 SPACE

SPACE

(1999).

________.

"Dinho Nascimento: Fábrica de Sons" [Dinho

Nascimento: Maker of Sounds]. Mundo SPACE SCapoeira

1, no. 1 (May 1999), 10-11.

Almeida,

Bira [Mestre Acordeon]. Capoeira: A Brazilian Art Form

(History, Philosophy, and SPACE

SPACE

Practice).

Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1986.

Amoruso,

Carol. "Cyro Baptista: Tarzan Percussionist of New

York’s Underground." Drum! 9, no. 5

SPACE (August/September 2000),

67-68, 70, 72, 75-76.

Balfour,

Henry. The Natural History of the Musical Bow.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1899.

Beyer,

Greg. "O Berimbau: A Project of Ethnomusicological

Research, Musicological Analysis, and SPACE

Creative Endeavor." DMA diss., Manhattan School

of Music, 2004.

________.

"Naná Vasconcelos: The Voice of the Berimbau."

Percussive Notes (October 2007): 48-52, SPACE

54, 56-58.

Capoeira,

Nestor [Nestor Sezefredo dos Passos Neto]. Capoeira:

Os Fundamentos da Malicia. Rio de SPACE

Janeiro: Susan Bach, 1992.

________.

The Little Capoeira Book. Berkeley: North Atlantic

Books, 1995.

________.

Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game. Berkeley:

North Atlantic Books, 2002.

Coelho,

Raquel. Berimbau. São Paulo: Editora Atica,

1993.

Consolmagno,

Peppe [Giuseppe Consolmagno]. "Il Berimbau" [The

Berimbau]. World Music 8, no. 33 SPACE

(August 1998): 44-52.

Cunha,

Tustão. "Como Montar e Cuidar do seu Berimbau"

[The Care and Assembly of a Berimbau]. SPACE

Batera & Percussão 4, no. 36

(August 2000), 44-45.

da

Anunciação, Luiz Almeida. "Birimbau from

Brazil: What is Birimbau and How to Play it?" SPACE

SPACE Percussionist

8, no. 3 (March 1971): 72-77.

________.

A percussão dos ritmos brasileiros sua técnica

e sua escrita. Caderno 1: O berimbau SPACE

(The Percussion Instruments of the Brazilian

Typical Rhythms: Its Techniques and its Musical SPACE

Writing. Book 1: The Berimbau). Rio de Janeiro:

Europa Empresa Gráfica e Editora, 1990.

Damaria,

Alexandre and Luiz Roberto Cloce Sampaio. O Berimbau-Brasileiro.

Everett: HoneyRock SPACE

Publishing,

2012.

de

Assis, Gilson. Brazilian Percussion. Munich: Advance

Music, 2003.

Debret,

Jean-Baptiste. Voyage pittoresque et historique au Bresil

[A Picturesque and Historical SPACESVoyage

to Brazil]. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères, 1834.

Faleiros,

Gustavo. "Papete: Música e Pesquisa" [Papete:

Music and Research]. Batera & Percussão

4, SPACE no. 32 (April 2000),

16-20.

Galm,

Eric A. "The Berimbau de Barriga in the World

of Capoeira." M.A. thesis, Tufts University, SPACE

1997.

________.

"Beyond the Roda: The Berimbau de Barriga

in Brazilian Music and Culture." Ph.D. diss., SPACE

Wesleyan University, 2004.

________.

The Berimbau: Soul of Brazilian Music. Jackson:

University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

________.

"Tension and 'Tradition:' Explorations of the Brazilian

Berimbau by Naná Vasconcelos, SPACE

Dinho Nascimento, and Ramiro

Musotto." Luso-Brazilian Review 48, no. 1

(2011): 79-99.

Germinario,

Fabio. "Luis Agudo." Jazzit 3, no. 6

(September/October 2001), 48-50, 52-53.

Gillette, Phillip."Airto Moreira and the Role of Brazilian Percussion in Early Jazz Fusion." M.A thesis, SPACE William Paterson University, 2021.

Gomes,

Sergio. "O berimbau" [The Berimbau]. Batera

& Percussão 4, no. 36 (August 2000), 40-42.

Graham,

Maria. Journal of a Voyage to Brazil. London: Longman,

1824.

Graham,

Richard. "Technology and Culture Change: The Development

of the Berimbau in Colonial SPACE

Brazil." Latin American Music Review

12, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 1991): 1-20.

Graham,

Richard and N. Scott Robinson. "Historical and Musical

Introduction to the Berimbau." LP SPACE

Highlights in Percussion 3, no. 1 (1988),

14, 16.

Herskovits,

Melville J. The Myth of the Negro Past. Boston,

MA: Beacon Press, 1958.

Jermano,

Rosario. 'Slide Berimbau'—Nuova Technica per suonare

il Berimbau ['Slide Berimbau'— SPACE

New Technique for Playing the Berimbau].

Rome: Rosario Jermano, 1999.

Koster,

Henry. Travels in Brazil. London: Longman, 1816.

Kubik,

Gerhard. Angolan Traits in Black Music, Games and Dances

of Brazil: A Study of African SPACE

Cultural Extensions Overseas. Lisbon:

Junta de Investigações Científicas

do Ultramar, 1979.

Lemba,

Deo. Meu Berimbau Instrumento Genial. Salvador:

Deo Lemba, 2002. [Instructional book & SPACE

CD].

Lewis,

J. Lowell. Ring of Liberation: Deceptive Discourse in

Brazilian Capoeira. Chicago: University SPACE

of Chicago

Press, 1992.

Merrell,

Floyd. Capoeira and Candomblé: Conformity and

Resistance Through Afro-Brazilian SPACE

SPACE

Experience.

Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2005.

Moreira,

Airto. Airto: The Spirit of Percussion. Wayne,

NJ: 21st Century Music Productions, 1985.

Nazário,

Zé Eduardo. "Entre Amigos: Zé Eduardo

Nazário entrevista Guilherme Franco" [Between

SPACE Friends: Zé

Eduardo Nazário Interviews Guilherme Franco]. Batera

& Percussão 4, no. 38 SPACE

(October 2000), 54-56.

Pellegrini,

Cecília. "Dinho Nascimento: Gongolô."

Revista Capoeira 2, no. 9 (2000), 28-29.

Pinto,

Tiago de Oliveira, editor. Brasilien: Einführung

in Musiktraditionen Brasiliens [Brazil: An SPACE

Introduction to the Music Tradition of Brazilians].

New York: Schott, 1986.

Rego,

Waldeloir. Capoeira Angola: ensaio sócio-etnográfico

[Capoeira Angola: Socio-Ethnographic SPACE

Essay]. Rio de Janeiro: Gráffica

Lux, 1968.

Robinson,

N. Scott. "Rhythm Legend Airto: Then & Now."

Modern Drummer 24, no. 6 (June 2000), SPACE

68-72, 74, 76, 78, 80, 82.

________.

"Naná Vasconcelos: The Nature of Naná."

Modern Drummer 24, no. 7 (July 2000), 98-102, SPACE

104, 106, 108.

________.

"The New Percussionist in Jazz: Organological and Technical

Expansion." M.A. thesis, SPACE

Kent State

University, 2002.

________.

"Okay Temiz: Drummer of Many Worlds." Percussive

Notes 41, no. 4 (August 2003): SPACE

28-30, 32-34.

Robinson,

N. Scott and Richard Graham. "Berimbau."

Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of SPACE

the World,

Volume 2: Performance and Production. Edited by John

Shepherd, David Horn, SPACE

Dave Laing,

Paul Oliver, and Peter Wicke. New York: Continuum, 2003,

345-349.

Rocca,

Edgard Nunes "Bituca." Escola Brasileira de

Música: uma visão Brasileira no ensino da SPACE

SPACE

música-ritmos

Brasileiros e seus instrumentos de percussão 1.

Rio de Janeiro: EBM, 1986.

Roisman,

Eli. "Dinho Nascimento: O mago do Berimbau" [Dinho

Nascimento: The Magician of the SPACE

Berimbau]. Batera & Percussão

4, no. 38 (October 2000), 32-34, 36.

Shaffer,

Kay. O berimbau-de-barriga e seus toques [The Berimbau

and Its Rhythms]. Rio de Janeiro: SPACE

Ministerio da Educação e Cultura,

1976.

Sharp, Daniel. Naná Vasconcelos' Saudades. New York: Bloomsbury, 2021.

Walsh,

Robert. Notices of Brazil in 1828 & 1829. London:

F. Westey & A.H. Davis, 1830.

Wetherell,

James. Brazil—Stray Notes from Bahia: Being Extracts

from Letters, & C., During a SPACEResidence

of Fifteen Years. Liverpool: Webb and Hunt, 1860.

Discography

Agudo,

Luis. Afrosamba & Afrorera. CD, Red RR123185.

1980/1984: Italy.

Agudo,

Luis and Afonso Vieire. Jazz a Confronto 33. LP,

Horo HLL 101-33. 1975: Italy.

Anderson,

Marc. Time Fish. CD, East Side Digital ESD 80842.

1993: USA.

Anugama.

Spiritual Environments: Shamanic Dream. CD, Higher

Octave 321. 2000: USA.

Australian

Art Orchestra and Sruthi Laya Ensemble. Into the Fire.

CD, ABC Classics ABC 465 705-2. SPACE

2000: Australia.

Baker,

Ginger. Horses & Trees. CD, Terrascape TRS

4123-2. 1986: USA.

Baptista,

Cyro. Vira Loucos: Cyro Baptista Plays the Music of

Villa Lobos. CD, Avant AVAN 061. SPACE

1997: Japan.

Benevides,

Kelly. Tráfego Local. CD, Via Som Music

VS 200215. 2001: Brazil.

Bernstein,

Chuck. Delta Berimbau Blues. CD, CMB Records 102844.

2009: USA.

Brock,

Jim. Pasajes. LP, Mbira MRLP-1001. 1988: USA.

Carmadelli,

Onias. Eu Bahia: Atabaque e Berimbau. LP, Philips

6470003. 1972: Brazil.

Codona.

Codona 2. CD, ECM 1177 78118-21177-2. 1981: USA.

Consolmagno,

Peppe [Giuseppe Consolmagno]. Timbri Dal Mondo.

CD, Cajù 4158-2. 1999: Italy.

Corrêa,

Djalma. Djalma Corrêa e Banda Cauim. LP,

Barclay 821 375-1. 1984: France.

da Costa,

Paulinho. Agora. CD, Pablo OJCCD-630-2 (2310-785).

1976: USA.

Daniele,

Pino. Pino Daniele. LP, EMI 3C 064-18391. 1979:

Italy.

Davis,

Miles. The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions. CD,

Columbia C4K 65570. 1969: USA.

________.

Big Fun. CD, Sony SRCS 5713. 1969/1972: USA.

de

André, Fabrizo. In Concerto (live). CD,

Ricordi 74321656992. 1999: Italy.

de

Oxossi, Camafeu. Berimbaus da Bahia. LP, Musicolor

104.405.016. 1967: Brazil.

Deguchi,

Khorey. Blowin’ Green Breeze. CD, MAHORA Japan

MFS-5801. 2000: Japan.

Eça,

Luíz and Sagrada Família. Onda Nova do

Brasil. CD, Lazarus Audio Products CD-2015. 1970: USA

SPACE (originally

released on LP as La Nueva Onda del Brasil on RVV

RVV-1136 in Mexico by Luiz SPACE

Eca Y

La Familia Sagrada).

Eloah.

Os Orixas. LP, Som Livre 403.6153. 1978: Brazil.

Favata,

Enzo. Il cielo è sempre piu' blu. CD, San

Isidro SND 1001-2. 1996: Italy.

Feijó,

Mônica. Aurora 5365. CD, Sonopress MRO178.

2000: Brazil.

Felicidade

a Brasil. Felicidade a Brasil. CD, Pulp Flavor

M01221635. 1973: France.

Floridos,

Floros with Nicky Skopelitis and Okay Temiz. Our Trip

So Far. CD, M Records SPACE

SPACE

SPACE 520167601013.

2000: Greece.

Franco,

Guilherme. Capoeira: Legendary Music of Brazil.

CD, Lyrichord 7441. 1997: USA.

Gil, Gilberto.

Gilberto Gil. LP, PolyGram 1029. 1968: Brazil.

Gilberto,

Astrud. Look to the Rainbow. CD, Verve 821556-2.

1965: USA.

Goodhart,

Rich. The Gathering Sun. CD, Beginner’s Mind

Productions BMP 0404. 1999: USA.

Graham,

Richard P. Lexicon. Cassette, Bearsville Music

01. 1988: USA.

Guzman,

Viviana. Planet Flute. CD, Well-Tempered 5187.

1997: USA.

Harmer,

Michael. Shamanic Journey Tapes: Musical Bow for the

Shamanic Journey. Cassette, SPACE

SPACE

The Foundation

for Shamanic Studies No. 6. 1991: USA.

Headhunters,

The. Survival of the Fittest. CD, BMG France 74321409522.

1975: USA.

Holland,

Mark & N. Scott Robinson. Wind & Fire.

CD, Cedar n Sage Music CS 7514. 2009: USA.

________.

Lost In The Beauty Of It All. CD, Cedar n Sage

Music CS 7517. 2013: USA.

Ipanemas,

Os. Os Ipanemas. CD, Mr. Bongo MRBCD001. 1962:

Brazil.

Jobim,

Antonio Carlos. Urubu. LP, Warner Archives BS-2928.

1976: USA.

Jones,

Elvin. Mr. Thunder. LP, East West EWR7501. 1974:

Sweden.

Jones,

Marti. Used Guitars. CD, A&M 5208. 1988: USA.

Klug,

Slats and Friends. A Brown County Christmas, Volume

Two. CD, Rebo Music 1231. 2001: USA.

Kodo.

Mondo Head. CD, SME SICP-1. 2001: Japan.

Kokelaere,

François. Berimbau: The Art of Berimbau (Brazilian

Musical Bow). CD, Musique du Monde SPACE

92678-2. 1993:

France.

L.A.

Four, The. The Scores. CD, Concord Jazz 6008. 1974:

USA.

Leonhart,

Michael. Glub Glub Vol. II. CD, Sunnyside SSC 1077.

1996: USA.

Liotta,

Saro. L’attesa. LP, RCA TPL1-1209. 1976: Italy.

Lunar Bear

Ensemble. Lunar Bear Ensemble. CD, Muworks CD 1006.

1988: USA.

Maeda,

Yuki. Jazz Age: Gershwin Song Book I. CD, Ewe EWCD002.

1997/1998: Japan.

Maria,

Marcia. Marcia Maria. LP, Capitol 31C 062 421130.

1978: Brazil.

Mendilow,

Guy. Live. CD, Earthen Groove Records EGR003. 2004:

USA.

Mendes,

Sergio. Primal Roots. LP, A&M 4353. 1972: USA.

Metheny,

Pat and Lyle Mays. As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita

Falls. CD, ECM 78118-21190-2. SPACE

SPACE 1981: USA.

Moraz,

Patrick. Patrick Moraz. LP, Charisma 0798. 1978:

UK.

Moreira,

Airto. Natural Feelings. LP, Buddah BDS-21-SK.

1970: USA.

________.

Life After That. CD, Narada World 724359326726.

2003: USA.

Musotto,

Ramiro. Sudaka. CD, Fast Horse 5. 2003: USA.

Nascimento,

Dinho. Berimbau Blues. CD, Velas V 20166. 1996:

Brazil.

________.

Gongolô. CD, Genteboa GB 002. 2000: Brazil.

Nascimento,

Milton. Tostão, a fera de ouro. LP, Odeon

7BD1202. 1970: Brazil.

________.

Miltons. CD, Columbia CK 45239. 1989: USA.

OM. OM

with Dom um Romão. LP, ECM 19003. 1977: USA.

Oriental

Wind. Life Road. CD, JA & RO 08-4113. 1983:

Sweden.

Papete

[José de Ribamar Vianna]. Berimbau e Percussão:

Music and Rhythms of Brasil. CD, Universal SPACE

Sound US CD7.

1975: Brazil.

________.

Planador. LP, Continental 1.01.404.244. 1981: Brazil.

Passport.

Iguaçu. CD, Wounded Bird WOU 149. 1977:

USA.

Pertout,

Alex. Alex Pertout. CD, Larrikin Entertainment

LRJ-273. 1993: Australia.

________.

From the Heart. CD, Vorticity Music VM 010116-1.

2001: Australia.

Pike

Set with Baiafro, The New Dave. Salomão.

LP, MPS MB-21541. 1972: Germany.

Powell,

Baden. Os Afro-Sambas. CD, Forma FM-16. 1965: Brazil.

Purim,

Flora. 500 Miles High: Flora Purim at Montreux.

CD, Milestone OJCCD-1018-2 (M-9070). SPACE

1974: USA.

Qureshi,

Taufiq. Rhydhun: An Odyessy of Rhythm. CD. CMP

CD 81. 1995: India/Germany.

Rebelo,

Nuno. Azul Esmeralda. CD, Ananana AN-LLL0001-CD.

1998: Portugal.

Redmond,

Layne and Tommy Brunjes. Trance Union. CD, Golden

Seal CD 0100. 2000: USA.

Red Red

Meat. There’s a Star Above the Manger Tonight.

CD, Sub Pop 387. 1997: USA.

Robinson,

N. Scott. World View. CD, New World View Music

NWVM CD-01/United One U1CD 402 SPACE

4569 3027 2.

1994: USA/Germany.

________.

Things That Happen Fast. CD, New World View Music

NWVM CD-02. 2001: USA.

Romão,

Dom um. Dom Um. LP, Mercury 528 122-1. 1964: Brazil.

Rudolph,

Adam. Adam Rudolph’s Moving Pictures. CD,

Flying Fish FF 70612. 1992: USA.

Sepultura.

Roots. CD, Roadrunner 8900. 1996: USA.

________.

Under a Pale Grey Sky. CD, Roadrunner 618436. 2002:

USA.

Shepp,

Archie. The Cry of My People. LP, MCA 23082. 1972:

USA.

Soulfly.

Soulfly. CD, Roadrunner 8596. 1998/1999: USA.

________.

Primitive. CD, Roadrunner 8512. 2000: USA.

________.

3+4. CD, Roadrunner International 84555. 2002:

USA.

________.

Tribe. CD, 404 Music Group 8020. 2002: Australia.

Temiz,

Okay. Drummer of Two Worlds. LP, Finnadar SR 9032.

1975/1980: Turkey.

________.

Oriental Wind. LP, Sonet SNTF 737. 1977: Sweden.

________.

Magnet Dance. CD, Tip Toe TIP-888819-2. 1994: Germany.

________.

Okay Temiz’s Magnetic Band: Magnet Dance.

CD, Vasco de Gama VDFCD 8000. SPACE

SPACE

1994: Turkey.

Tibbetts,

Steve. Exploded View. CD, ECM 1335 831 109-2. 1986:

USA.

Tucan Trio.

Tucan Trio. CD, Nada NADA 16. 2000: Israel.

Various

Artists. The Discoteca Collection: Missão de

Pesquisas Folclóricas. CD, Rykodisc RCD 10403.

SPACE 1938:

Brazil.

________.

Folklore e Bossa Nova do Brasil (Jazz Meets the World

1: Jazz Meets Brasil). CD, MPS SPACE

533 133-2.

1966: Germany.

________.

Irmãos Coragem.

LP, Philips 765.119. 1970: Brazil (unidentified berimbau

player).

________.

Berimbau e Capoeira—BA. CD, Documentario Sonoro

do Folclore Brasileiro INF 46. SPACE

1988: Brazil.

Vasconcelos,

Naná. Africadeus. CD, Saravah SHL 38. 1972:

France.

________.

Amazonas. LP, Phonogram 6349.079. 1973: Brazil

________.

Saudades. CD, ECM 1147 78118-21147-2. 1979: USA.

________.

Nanatronics: Rekebra/Nanatroniko. LP (12"

single), Bagaria BAG-X 0190784. 1984: Italy.

Vasconcelos,

Naná and Agustin Pereyra Lucena. El Increible

Naná con Agustin Pereyra Lucena. SPACE

SPACE

LP, Tonodisc

TON-1020. 1971: Argentina.

Vazquez,

Santiago. Raamón. CD, Lal 025. 2004: Argentina.

Veloso,

Caetano. Transa. CD, Polygram 838511. 1972: Brazil.

Voicequn.

Peace Birthday. CD, Funny Time Label & Records

SB-202. 2002: Japan.

Watson,

David. Skirl. CD, Avant 77. 1999: USA.

Weather

Report. Weather Report. CD, Columbia/Legacy CK-48824.

1971: USA.

________.

Live in Tokyo. CD, Sony International 489208-2.

1972: Japan.

Yamamura,

Seichi. Voice of TEN. CD, Funny Time Label &

Records HOC-356. 1997: Japan.

Videography

Acuña,

Alex. The Rhythm Collector. 2007. Drum Workshop

(DVD). (Alex Acuña-berimbau).

Almeida,

Bira [Mestre Acordeon]. Capoeira Bahia. 1983. World

Capoeira Association (video).

Cortesão, Jorge. The Berimbau—volume 1.

1999. Bridges to Productions (video).

________.

The Berimbau—volume 2. 1999. Bridges to Productions

(video).

Damaria,

Alexandre and Luiz Roberto Cloce Sampaio. O Berimbau-Brasileiro.

Everett: HoneyRock SPACE

Publishing,

2012.

Duarte,

Anselmo. O Pagador de Promessas. 1962 (film).

Duarte,

Cassio. Introduction to Brazilian Percussion. 2003.

LP LPV136-D (DVD).

Gil,

Gilberto. Electracústico. 2004. WEA 5050467761025

(DVD & CD set).

Lenine

(Oswaldo Lenine Macedo Pimentel). Cité.

2004. BMG AA0025000 (DVD).

Lettich,

Sheldon (director). Only the Strong. 1993. 20th

Century Fox (DVD).

Moreira,

Airto and Flora Purim. The Latin Jazz All-Stars Live

at the Queen Mary Jazz Festival. SPAC1985.

View NTSC1311 (video).

Musotto,

Ramiro. Sudaka: Ao Vivo. 2005. MCD MCD 304 (DVD

& CD set).

Santo,

Joselito Amen. Sounds of Bahia: Introduction to Berimbau.

2006. Play My Game (DVD).

Sembello,

Michael. The Bridge. 1998. PBS (video).

Various

Artists. Bahia de Todos os Sambas. 1983. Sagres

(video).

________.

Woodstock Jazz Festival. 1981. Pioneer Artists

PA-98-596-D (DVD).

________.

The Spirit of Samba: Black Music of Brazil. 1982.

Shanachie (video).

________.

The JVC Video Anthology of World Music and Dance. Vol.

28: The Americas 2. 1988. SPACE

JVC, Victor

Company of Japan (video).

________.

Batouka: First International Festival of Percussion.

1989. Rhapsody Films (video).

________.

The Music of Jimi Hendrix. 1995. TDK (DVD).

________.

Pernambuco em concerto. 2000. África Produçoes

(video).

Vasconcelos,

Naná. Berimbau. 1971. New Yorker Films (documentary

film).

________.

Goree, On the Other Side of the Water. 1990. UNESCO

(documentary film).

©2000

- N. Scott Robinson. All rights reserved.

|